Edward "Mick" Mannock

Top British Ace, 61 victories

By Stephen Sherman, Aug. 2001. Updated April 11, 2012.

Like many aces in both World Wars, Mannock was one of those who demonized and depersonalized his enemies. After machine gunning the two occupants of a downed German plane, Mannock explained "The swines are better dead - no prisoners." Interestingly, he combined this implacable hatred for German members of the human race with an abiding faith in the Labour Party's promise of social justice for workers.

Whatever his motivations, he was the highest scoring British ace of the First World War, credited with 61 German aircraft. (Many sources say 73, but the noted historian and author Norman Franks has determined 61 to be more accurate.)

Youth

Edward Mannock was born in Ballincollig, Co. Cork, Ireland on May 24, 1887, thus the nickname "Mick." (There has been some confusion on this, with some sources claiming he was born in Aldershot, England. But an informed email correspondent noted that Mannock's s birth certificate clearly referred to his Irish birth.) Mick was the son of a Scots professional soldier and an English mother. His father, a hard-drinking brutal man, abandoned his family when Mick was twelve. Almost blind in his left eye (one would think a nearly impossible defect for a fighter pilot to overcome), the youngster took any job he could find and eventually boarded with a childless couple. By age 20, Mannock had joined the Labour Party and burned with a sense of social injustice.

The outbreak of the war caught him working in Turkey. The Turks interned him and he rapidly declined in their loathsome prisons. Near death, the Turks repatriated him and in 1915 in joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. By 1916, he had become an officer. At age 29 and with a bad eye, he made an unlikely candidate for pilot training, but in the pressing demand for fliers, he was accepted. The story is told that he memorized the eye chart while reading it with his good eye.

Royal Flying Corps

He was made a flying officer in February, 1917, with the Joyce Green Reserve Squadron. During his first solo in an Airco DH-2 pusher biplane, he got into a spin at 1,000 feet, and recovered, but got in trouble with his CO, Major Keith Caldwell, who suspected Mick of showboating. But he soon got on well with the Major, before transferring to the RFC's Nieuport-equipped 40th Squadron. Caldwell described Mick as "very reserved, inclined toward a strong temper, but very patient and somewhat difficult to arouse."

At 40th Squadron, the reserved Mannock didn't fit in right away. On his first night, he inadvertently sat down in an empty chair, a chair which a newly fallen flier had occupied until that day. At first, Mick held back in the air, too, to the extent that some pilots thought he was yellow. He admitted that he very frightened. Finally, on May 7, he shot down an observation balloon and thought this would gain him the acceptance of the squadron. That night at dinner, silence again. Only this time it was no faux pas of Mannock's; the beloved ace, Albert Ball, had been shot down. Mick wept.

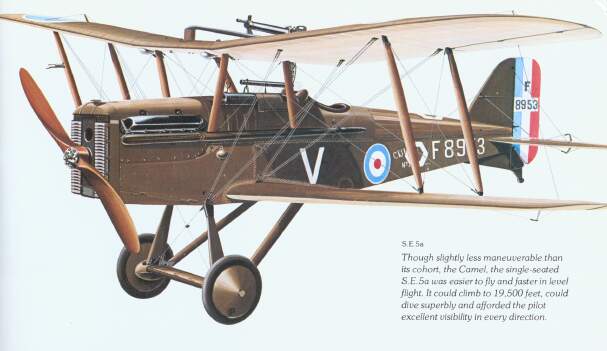

He kept flying and conquered his fear. He worked tirelessly at gunnery practice and forced himself to get close to the German airplanes. After one kill, he coldly described it. "I was only ten yards away from him - on top so I couldn't miss. A beautifully colored insect he was - red, blue, green, and yellow. I let him have 60 rounds, so there wasn't much left of him." He kept downing Germans; by July he had earned the Military Cross. He was grimly determined to bring down the German Empire. His determination, flying skills, and sense of teamwork earned him a promotion to Captain. At the end of the year, the squadron transitioned to SE-5a's. (One of the best fighters of the war, over 5,000 S.E.5's were produced. It's dihedral upper wing, with a Lewis gun perched atop it, was distinctive. Capable of 135 MPH, it was one of the speediest planes of the era.)

In March, 1918, with twenty-three kills to his credit, Mannock was appointed flight commander of the new 74th Squadron. He continued as always, shooting down Germans, but never hogging credit, carelessly letting newer fellows get credit for kills. But in three months, he claimed thirty-six more, bringing his total to fifty-nine. He was an excellent CO; he took a very protective attitude toward his fliers and lectured them on survival and success. "Sight your own guns," he told them, "The armourer doesn't have to do the fighting."

He became obsessively fearful of one thing - a flaming death. It was a horror he had seen and inflicted often enough. He took to carrying a loaded pistol with him. "They'll never burn me," he resolved.

His hatred of the Germans grew, "I sent one of them to Hell in flames today ... I wish Kaiser Bill could have seen him sizzle." Once he forced a German two-seater to crash. Most pilots would have been satisfied with that, but not Mick. He repeatedly machine-gunned the helpless crew. When his squadron mate questioned this behavior, Mannock explained "The swines are better dead - no prisoners." Another time he pursued a silver Pfalz scout; the two planes rolled, dived, looped and firing. Eventually Mick got the better of his opponent and the German started twisting and turning as it fell toward a certain crash. Mick stayed on it, firing away, "a really remarkable exhibition of cruel, calculated Hun-strafing" another pilot called it. On this day, Mannock shot down four planes. He delightedly announced to the mess hall, "Flamerinoes - four! Sizzle sizzle wonk!" Van Ira, a South African flier in the 74th commented on Mannock's success:

"Four in one day! What is the secret? Undoubtedly the gift of accurate shooting, combined with the determination to get to close quarters before firing. It's an amazing gift, for no pilot in France goes nearer to a Hun before firing than [Mannock], but he only gets one down here and there, in spite of the fact that his tracer bullets appear to be going through his opponent's body."

Mannock was awarded the D.S.O. not long after his four-in-a-day feat.

|

Mick Mannock - from 1935 Hall of Fame of the Air cartoon feature, click for large view |

Mid 1918

By this time, the strain of combat flying and the fear of his own fiery death got to Mannock. But he kept flying, repeatedly scoring multiple kills. He fell sick with the flu, aggravated by tension. By June, 1918, he had made 59 kills, and had also earned a home leave. When he left the 74th Squadron, he wept publicly. On starting his third tour of duty in July, as CO of the 85th Squadron, he confided his mortal fears to a friend, worried that three was an unlucky number. He became obsessed with neatness and order; his hair, his medals, his boots, everything had to be 'just so.' The death of his friend, and fellow top ace, James McCudden, on July 8th, profoundly affected him.

But he kept going and he kept destroying enemy airplanes. When he shot down an aircraft on July 22, a friend congratulated him. "They'll have the red carpet out for you after the war, Mick." But Mannock glumly replied, "There won't be any 'after the war' for me."

He befriended a New Zealand flier, Lt. Donald Inglis, as if to replace McCudden. On July 26, the two went up, and Mannock let Inglis finish off a German plane. The two destroyed one German plane, and then a second on their way home. Inglis described what happened after the second kill:

Falling in behind Mick again we made a couple of circles around the burning wreck and then made for home. I saw Mick start to kick his rudder, then I saw a flame come out of his machine; it grew bigger and bigger. Mick was no longer kicking his rudder. His nose dropped slightly and he went into a slow right-hand turn, and hit the ground in a burst of flame.

I circled at about twenty feet but could not see him, and as things were getting hot, made for home and managed to rech our outposts with a punctured fuel tank. Poor Mick ...the bloody bastards had shot my Major down in flames.

As so often the case, the exact cause of the great ace's death remains uncertain. Anti-aircraft fire? The German pilot? A lucky shot from an infantryman? Did he die the flaming death that he so feared? Or did he use his pistol?

A year later, he was awarded the Victoria Cross, for his sixty-one kills, his "fearless courage, remarkable skill, devotion to duty, and self-sacrifice."

Sources:

- The Aerodrome

- Heroes of the Sunlit Sky, by Arch Whitehouse, Doubleday, 1967

- The Canvas Falcons, by Stephen Longstreet, Barnes & Noble, 1970

- Knights of the Air, by Ezra Bowen, Time-Life Books, 1980

- Rand McNally Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft: 1914-1980, by Enzio Angelucci, The Military Press, 1983