Tirpitz

German Battleship of WW2

By Stephen Sherman, June, 2011. Updated March 21, 2012.

The Tirpitz outlasted her more famous sister ship Bismarck, but ultimately met the same fate when she was sunk by British airplanes in a Norwegian fjord in 1944.

General Description

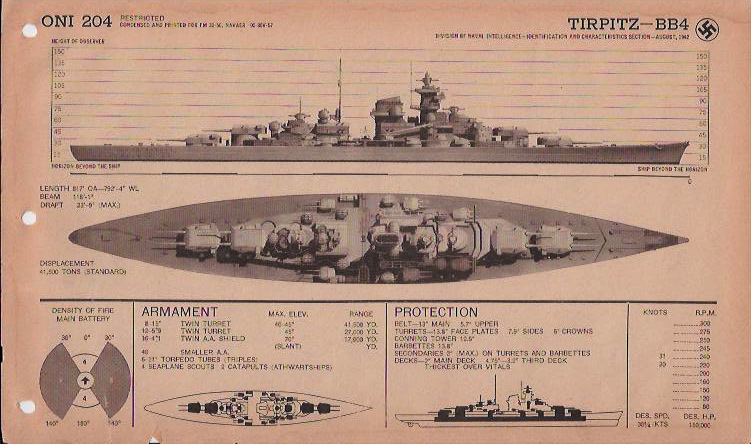

Her overall profile gave a sloped appearance, the only abrupt break being a gap amidships for her catapult. Two turrets sat forward of gradually rising decks, with a modest-height conning tower aft. From her funnel, her profile slanted downwards, from some superstructure to two after turrets.

Tirpitz' overall length was 817 feet, 792 feet 4 inches at the waterline, with a beam of 118 feet 1 inch. Her maximum draft was 33 feet 9 inches and she displaced 41,500 standard tons (although officially stated as 35,000 tons per the Washington Naval Treaty). Her main armament consisted of eight 15-inch guns mounted in four double turrets; these guns could be elevated to 40-45° and had a maximum range of 41,500 yards. Her secondary weapons were twelve 5.9 inch guns, mounted in six double turrets. These had a maximum elevation of 45° and could reach 27,000 yards. Tirpitz featured abundant anti-aircraft defenses: sixteen 4.1 inch guns clustered amidships in twin shields with a 70° maximum elevation that could range up to 17,000 yards, and forty smaller AA guns around the decks. Her armor protection was heaviest in the main waterline belt (13 inches), turret face plates (13.8 inches), barbettes (13.8 inches), and the conning tower (12.6 inches). The sides of the turrets were covered by 7.9 inches of steel and their crowns by 6 inches. Deck armor varied from 2 inches to 4.75 inches over the vitals.

Her designed horsepower was 150,000 HP, at which she could steam just over 30 knots - quite fast for a battleship.

Operational History

For most of her wartime career, Tirpitz sat in Norwegian fjords, an ongoing threat to the Royal Navy and a constant target for British attacks.

Tirpitz was laid down by Kriegsmarinewerft, in Wilhelmshaven on October 24, 1936 and was launched on April 1, 1939. Her launching was a huge ceremony, all the top Nazi brass showed up and Erich Raeder was promoted to Gross-admiral. Almost two years later, on February 25, 1941, she was commissioned and sent to the Baltic for sea trials. After transiting the Kiel Canal, Tirpitz tested her machinery and guns for several months. By this time, Hitler had invaded Russia, and Tirpitz's first combat deployment was in September, 1941, when she and other ships were assigned to prevent Soviet warships from leaving Kronstadt.

The sinking of the Bismarck in May, 1941 had made a powerful impression on the German leaders, and the question of what to do with Tirpitz came up. To send her out in the North Atlantic, and most likely follow Bismarck "to the bottom of the sea," wasn't the answer. Admiral Raeder proposed to send her to Norway, where, merely by being there (the "fleet in being" concept) she would tie up British naval resources. The Royal Navy couldn't very well ignore a Bismarck-class battleship stationed near the North Sea and athwart the convoy routes to Murmansk. These discussions were going on in late 1941. Hitler agreed to send Tirpitz to Norway, but less because of Raeder's sound strategic thinking that due to his own intuition that British were going to counter-attack in Norway.

In January 1942, she went back through the Kiel Canal, and on the 16th arrived with her escorts in Fættenfjord near Trondheim, Norway.

The Hunt for Convoy PQ-12

On March 1 1942, British Convoy PQ-12 set off for Russia, escorted by the battleship Duke of York, the battle-cruiser Renown, one cruiser, and six destroyers. It was planned to rendezvous (or at least pass close by) westbound convoy QP-8 on March 7 off Bear Island. Tirpitz was assigned to go after PQ-12 (Operation Sportpalast) and put out on March 6, accompanied by destroyers. The Royal Navy knew Tirpitz' intention and dispatched a second group from Home Fleet to deal with the threat: battleship King George V, aircraft carrier Victorious, one cruiser, six destroyers. So, at this time, there were two Allied merchant convoys, two Allied battle groups, and one German battle group in the same area; the convoys doing their best to avoid enemy contact, the warships all prowling for the enemy. On March 7, the two convoys met as planned, while the Tirpitz was 100 miles to the south and Admiral Tovey's King George V group was approaching form the west. While the three forces probed for each other they did not meet, the only loss being the Russian Izhora straggling from convoy. This continued on the eighth, as Tirpitz hunted for PQ-12 off Bear Island and Tovey's force searched for Tirpitz. Throughout these two days, there were near-misses and close calls, but the warships never encountered each other.

On March 9, Fairey Albatross torpedo biplanes from Victorious finally located Tirpitz, who readied her anti-aircraft defenses and launched two Arado 196A-3 seaplanes for combat air patrol. Soon a flight of twelve Albatrosses came after the battleship and launched torpedoes. Two of them were shot down and none of the torpedoes hit their target, but now the Tirpitz had been spotted and British naval air and surface forces were in the area. The Tirpitz beat a hasty retreat to Vestfjord near Bogen, and escaped without any further contact or damage. She soon made her way back to her permanent anchorage off Trondheim.

While the convoys also suffered little loss, the British now had to confront the menace of the Tirpitz, and tried to bomb her. But she was well-defended. Situated in fjord with steep mountains close on either side and with frequent bad weather, Tirpitz was hard to approach from the air at all. To this, the Germans added a host of anti-aircraft guns around the fjord and, when an air raid was signaled, they fired up dense and effective smoke screens. During late March and April of 1942, Bomber Command launched three air raids against Tirpitz, a total of 107 aircraft; 12 were shot down and none did any damage.

Convoy PQ-17

The destruction of this convoy in July, 1942 was Tirpitz' greatest, if indirect, success. Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the event, "one of the most melancholy naval episodes in the whole of the war."

In June, the Germans became aware that convoy PQ-17, consisting of 35 merchantmen plus escorts, would be heading for Russia late in the month. They assembled two battle groups to attack it: Battle Group 1 centered on Tirpitz, and Battle Group 2 centered on Lützow. These forces sortied on July 5, but some ships ran aground, others had mechanical problems; only Tirpitz, 2 cruisers, six destroyers managed to get out to the sea lanes. They headed for Bear Island, where convoy PQ-17 was reported, but aware that they had been spotted, returned to base the next day. Meanwhile the British understood that Tirpitz was preparing to attack the convoy. On this basis, the order was given for the convoy to scatter (a decision that has been subsequently questioned and challenged). For the merchant ships and their crews, the result was deadly. German aircraft and submarines, working together, sank 24 of the 35 ships.

And it all happened because the Admiralty thought that Tirpitz was in the area.

Chariots of Water

In late October, the British attempted to attack Tirpitz with two "Chariots," torpedoes rigged for frogmen to ride and guide toward a target, in a mission codenamed Operation Title. They fitted out a fishing boat, the Arthur, to get close enough to Tirpitz to launch the Chariots. Somewhat surprisingly, Arthur got within ten miles of the great battleships undetected, but rough seas had torn loose the torpedoes. The mission was a flop. The crew scuttled Arthur and made their way to neutral Sweden.

X-Craft Attack

The British devoted boundless energy and ingenuity to attack Tirpitz. In addition to surface warships, conventional submarines, aircraft, and human "Chariot" torpedoes, in 1943 they also tried midget submarines, dubbed "X-Craft." The midget subs were to be towed from the UK to just outside the Norwegian fjords, set loose to enter the fjords under their own power, approach the Tirpitz, Scharnhorst, and Lützow, drop timed explosive charges right under the ships, and then withdraw. This mission was known as "Operation Source." Conditions of weather, darkness, and moonlight permitted a window of opportunity for this attack between September 20 and 25, 1943. One conventional submarine towed each X-craft. Submarines Thrasher, Truculent, and Stubborn towed X-5, X-6, and X-7 respectively, which aimed at Tirpitz. Syrtis and Sceptre towed X-9 and X-10, which were for the Scharnhorst. And Sea-nymph towed X-8, which was to attack Lützow.

Setting out on September 11 and 12, the towing aspect itself was hazardous, and both X-8 and X-9 were lost en route to Norway. After various problems, the remaining four X-craft arrived off Kåfjord on September 20 and their mission crews were put aboard. X-5 (Lieutenant Henty-Creer) exchanged shouts of good luck with X-7 (Place), but was never heard from again and the craft has never been found. X-6 (Lieutenant Cameron) made good progress, submerged, and by dusk she was off the entrance to Kåfjord. X-7 (Lieutenant Place) had an uneventful passage up to the appointed rendezvous point, but never met up with the other X-craft. X-10 (Lieutenant Hudspeth) had mechanical problems and was forced to retire to a sheltered fjord, attempt repairs, and then attack Scharnhorst.

Thus, on the morning of September 20, the midget subs X-6 and X-7 were near enough Tirpitz to carry out their plan. X-6 got close, became entangled in the anti-sub nets, and under a hail of small-arms fire and grenades, managed to drop her explosive charges underneath Tirpitz. The crew was compelled to scuttle their craft and surrender, although their pleased demeanor suggested to the Germans that they had accomplished their goal. X-7 also got close enough to Tirpitz to drop her charges. After doing so, X-7 got back out through the anti-sub nets, but was so heavily damaged that it sunk, and its crew also surrendered.

Just after eight o'clock that morning a tremendous explosion rocked the Tirpitz. The midget midget sub attack had worked! While the Tirpitz did not sink, the damage to the hull, electrical generators, and propeller shafts was extensive and took six months to repair. She did not put to sea again until Spring 1944.

Operation Tungsten

By early April 1944, the British knew that the repairs to Tirpitz were nearly complete and that she was about to put to sea. (The British had cracked the German Enigma radio-encryption system, and knew much of German intentions throughout the war.) They employed the two fleet carriers Victorious and Furious, four escort carriers (Emperor, Searcher, Fencer and Pursuer), and supporting cruisers and destroyers. Keenly aware of the vulnerability of radio communications, the force observed strict radio silence en route, while decoy stations emulated the ships' routine messages at Scapa Flow.

Thus, on the early morning of April 3. the Royal Navy approached the Tirpitz at Kåfjord unobserved. Their strike force included 40 Barracuda torpedo bombers and 40 escorting fighters (Corsairs, Wildcats, and Hellcats), which would go off in two waves. The strike aircraft carried a mix of four different types of bombs, to maximize the damage to their target. At 5:29, with complete surprise, the first wave of British aircraft swept over Kåfjord, some fighters high overhead providing top cover, other fighters coming in low strafing the decks of the battleship, and the Barracudas dropping their mix of bombs. In one minute, they had passed, and an hour later, the second wave struck in the same way.

The damage was considerable. 122 men were killed, two of the 5.9-inch gun turrets were destroyed, fires broke out, and boilers were destroyed. The British had originally planned a second day of strikes, but considering the significant damage done, Admiral Moore decided to return then, and by April 6 the force was back in Scapa Flow.

It was now apparent that, lacking suitable air cover, the Tirpitz could never put to sea, but Admiral Doenitz was adamant that she be repaired. Destroyers ferried repair crews and equipment up from Kiel, and by July, the repairs had been complete.

The End - Lancasters and Tallboys

The British also developed extremely powerful, penetrating bombs during the war: "Tallboy" bombs with 5,000 pounds of explosives and highly accurate (by WW2 standards). Lancaster and Wellington bombers were able to carry the giant bombs and in September, 1944, the first "Tallboy" equipped mission was planned. At that time, Tirpitz was still in Kåfjord, beyond the round-trip range of the RAF bombers. Arrangements were made for them to touch down at a Yagodnik, a base in northwestern Russia. On September 10, the first such mission took place, but without any real damage to Tirpitz. On September 15, the second mission, Operation "Paravane" went off. This time, they severely damaged her bow, but given the difficulties of bomb-damage assessment, the British were not sure of the results. But the Germans were, and realized the seriousness of the threat. It seemed advisable to relocate Tirpitz to shallower waters, where, in any event, she would not be sunk.

Thus she was moved to Tromso, which happened to be 200 miles closer to the British Isles, putting the target just within the extreme round-trip range of the Lancaster and Wellington bombers. On November 12, the third and last Tallboy bombing mission against the Tirpitz (Operation Catechism) was organized. 32 Lancasters took off in the pre-dawn hours, and arrived over the Tirpitz at 9:41. Bombs away! At least two hit the ship, which began listing heavily to port. Within minutes, she rolled over and capsized, too quickly to abandon ship. 1000 of her 1700 crew died. A few dozen were rescued by cutting through the exposed, overturned hull.

That was the end of Tirpitz.

After the war, a Norwegian company purchased salvage rights to the ship, and from 1949 through 1957 cut up the wreckage. I understand that bits of the Tirpitz can still be bought in Norway.