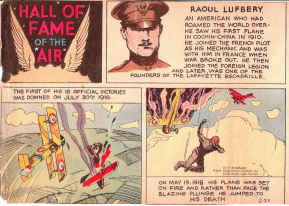

Raoul Lufbery

Leading Ace of the Lafayette Escadrille

By Stephen Sherman, Aug. 2001. Updated April 16, 2012.

According to all reliable sources, Raoul Lufbery did not invent the defensive aerial tactic known as the Lufbery circle and Max Immelmann didn't invent the Immelmann turn. And, while Lufbery called Wallingford, Connecticut his home, he spoke French better than English, he was born in France, and he shot down all but one of his seventeen official scores in French service.

Gervais Raoul Lufbery was born on March 14, 1885 in France.

His father moved to Connecticut where he set up a stamp dealership, leaving Raoul in the care of his grandmother until he was nineteen, when he sailed for America. Ironically, his father sailed for Europe on the same day, and they never saw each other again. But Raoul stayed in Wallingford for two years, where he learned to speak a little English. He traveled to Cuba and back to the U.S., where a stint with the U.S. Army in the Philippines earned him American citizenship. Then he left for the Far East.

While in Indochina, in 1912, he met the renowned aviator Marc Pourpe, who was barnstorming Asia in his Blériot. He worked for Pourpe as foreman and mechanic. The two of them moved on to Europe and Africa. In Africa in 1913, Pourpe made the first round-trip Cairo-to-Khartoum flight, with Lufbery arranging for fuel, maintenance, and spare parts.

War

In August, 1914, Lufbery joined the French Foreign Legion as an infantryman, service which wouldn't jeopardize his American citizenship. Nonetheless, he was promptly transferred to Pourpe's squadron of the French aviation service as a mechanic. Within a few months Pourpe was dead and Lufbery had enrolled in pilot training at Chartres. After learning to fly on Farman, he joined Escadrille VB (Voisin) 106. He was a competent pilot and next applied to fly single seaters, fighters. After some opposition from his CO, he went to Plessis-Belleville for Nieuport scout training. He was not a naturally gifted pilot, but he was persistent and became a decent flier.

Lafayette Escadrille

The original enlistees in the Lafayette Escadrille were long on patriotism, idealism, and Ivy League education, but short on flying experience. The organizers of the American volunteer unit next recruited some men who knew something about flying. Lufbery fit the bill: he was an American citizen and he was an experienced combat pilot. He joined the Escadrille Lafayette, N.124, on May 24, 1916.

At first, he didn't quite fit in with the college boys at Luxeuil. He was several years older than most of them; he seemed crude and unfriendly at first. His first aerial victory came on July 30 over Verdun and his second later that same day. Apparently this success inspired him to log as many hours as possible aloft in his Nieuport, looking for enemy planes. By October 12, he had knocked down three more; he was an ace - the leading flier of the Lafayette Escadrille, famous in France and America. They continued flying through the snowy winter; Lufbery downed his seventh in January, 1917.

It is not known how the Lufbery circle became to be named for him. The defensive aerial tactic of planes forming a circle, with each protecting the tail of the one in front, had been known since the earliest days of formation flying.

By February 18, 1918, when the Lafayette Escadrille was re-organized into a unit of the United States Army, Lufbery shot down nine more planes, 16 altogether while flying French colors. He added just one more while with the U.S.

94th Aero Squadron

He was one of the first members of the Lafayette Escadrille to be selected for American service. He was given the rank of Major, and assigned to the as-yet unformed 94th Aero Squadron, and he began "flying a desk" for U.S. aviation headquarters at Issoudun. In early March, 1918, when the Germans staged their last big offensive of the war, he and other experienced American pilots had nothing to do. (The 94th, the "Hat in the Ring" squadron, included Eddie Rickenbacker and became the leading American squadron of World War One.) The 94th had some Nieuports, but no machine guns for them. "It's nearly a year since the United States declared war," Lufbery complained, "And what do you suppose the 94th is doing? Waiting for machine guns." Tired of waiting around, Lufbery led Rickenbacker and Doug Campbell flew the 94th's first (although unarmed) patrol on March 19.

But once he did begin flying with the 94th, for some reason he became moody and irritable. He worried about his Nieuport 28 and (like Mick Mannock) obsessed over a fear of fire in the air. On May 19, a Lieutenant Gude of the 94th went up to engage an Albatros two-seater over their airfield at Saint-Mihiel. This was Lt. Gude's first combat flight, and at first it seemed as if he had scored against the Albatros, but after spiraling downward the German pilot pulled out and headed for home.

Anxious to score over Allied lines, Lufbery took off after the escaping Albatros. The onlookers watched, expecting him to shoot down the German easily. He made one pass and then moved off, likely to clear a jammed gun. But the enemy gunner hit next and Lufbery's plane caught on fire. Lufbery was seen to climb out of the cockpit and jump, from about 200 feet above the village of Maron. He was impaled on a picket fence and his body recovered by a woman and her daughter. Billy Mitchell watched, and regretted that America's leading flier had not been carrying a parachute (not yet regulation equipment).

Some have speculated that Lufbery might have achieved greater things had he continued flying with France, rather for his adopted country.

Sources:

- The Aerodrome

- Heroes of the Sunlit Sky, by Arch Whitehouse, Doubleday, 1967

- The Canvas Falcons, by Stephen Longstreet, Barnes & Noble, 1970

- Knights of the Air, by Ezra Bowen, Time-Life Books, 1980

- Rand McNally Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft: 1914-1980, by Enzio Angelucci, The Military Press, 1983