René Fonck

Highest Scoring Allied Ace, 75 kills

By Stephen Sherman, Aug. 2001. Updated April 15, 2012.

While shooting down 75 German planes, René Fonck was never wounded and claimed that only one enemy bullet ever hit his airplane. He was methodical, detailed, a skilled marksman, and a braggart. He took pride in using the least amount of ammunition necessary to bring down an enemy. He was a fine flier, but his self-promotion won him few close friends.

He didn't drink or carouse with the other pilots, preferring to plan missions, perform calisthenics, and press his uniforms. In a remark that displayed both his skill and his boastfulness, he once said, "I put my bullets into the target as if by hand."

Background

René Paul Fonck was born on March 27, 1894, in Saulcy-sur-Merthe, a typical French village in the mountainous Vosges region. At 20, when the war started, he was assigned to the engineers and spent several months digging trenches, building bridges, and fixing roads.

In early 1915, he entered flight training, first at Saint-Cyr, then at Le Crotoy. His first combat unit was Escadrille Caudron 47 at Corcieux, flying a Caudron G.4 (an ungainly-looking bomber/reconnaissance plane: a twin-engined biplane, with a pilot nacelle instead of a full-length fuselage). He did fine work as an observation pilot, twice being mentioned in dispatches. He shot down his first enemy aircraft in July 1916, in a Caudron that had been fitted with a machine gun. But in his greatest feat in a G.4, he didn't fire a weapon at all. On August 6, he attacked a German Rumpler C-III. Maneuvering over and around the reconnaissance plane, he skillfully stayed out of its field of fire, while continually forcing it lower and lower. Eventually, the German had to land behind French lines; Fonck had captured a new, undamaged prize for the Allies to inspect.

Les Cigognes

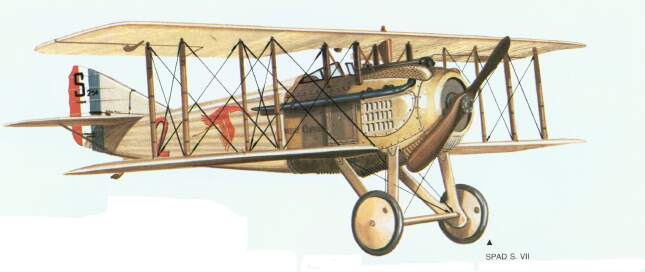

Following this, Fonck was transferred to Escadrille Spad 103, Les Cigognes, the Storks, France's premier fighter groups, comprised of escadrilles S.3, S.26, S.73, and S.103. After several months of training in single-seaters, he began flying Spads in May, 1917.

(In this month the ultimate version of the Spad, the S.XIII, began to be delivered to French units. Presumaby the Storks received early deliveries. Powered by a Hispano-Suiza 235 HP engine, capable of 138 MPH, the Spad S.XIII was the fastest aircraft of World War I. It weighed 1,800 pounds and was considered to be very rugged for that era. It carried two synchronized machine guns. The French built 8,472 of the S.XIII and it was the superior fighter plane for the remaining 18 months of the war. Fonck scored most of his kills in a Spad S.XIII.) In less than two weeks, he became an ace. By the fall of 1917, he had downed 18 German planes, and was inducted into the Legion of Honor.

Always anxious to prove his claims, on September 14, he recovered the barograph from an aircraft he had shot down. The instrument confirmed Fonck's rendition of the encounter, showing that the German plane had reached 20,000 feet, had maneuvered lower while dueling Fonck, had zoomed up briefly at 5,000 feet (as the pilot pulled back on the stick when hit), and then had stalled and crashed.

The great French ace, Georges Guynemer, disappeared on September 11. The Germans claimed that he was shot down by Kurt Wisseman, a Rumpler pilot, and a good one, as he was credited with five kills while flying the two-seaters. Shortly, Fonck achieved a measure of revenge for the French Aviation militaire. On the 30th, he spotted a two-seater flying at 9,000 feet. Sensing that the rear gunner was alert to him, he expertly moved in below and behind, where he could not be fired on. Fonck fired two bursts. The Rumpler fell inside the French lines and the dead pilot's papers identified him as Kurt Wisseman. He told a journalist that by killing "the murderer of my good friend," he had become "the tool of retribution." This statement might have surprised the dead Guynemer, since he and Fonck were never friends.

Fonck's Personality

One book referred to Fonck as "a dreadful show-off, intolerable, always bragging, egotistical, ham-like, a poseur, gaudy, loud, hard to take, expressionless at times, morose, deliberately cruel, over-neat, tightly tailored, etc." Even his best friend, Lt. Claude Haegelen, (a 22 victory ace), was quoted as saying of Fonck:

He is not a truthful man. He is a tiresome braggart, and even a bore, but in the air, a slashing rapier, a steel blade tempered with unblemished courage and priceless skill. ... But afterwards he can't forget how he rescued you, nor let you forget it. He can almost make you wish he hadn't helped you in the first place."

One has to wonder what his enemies said. The following excerpt from his memoirs reveals much of Fonck's character.

An Excerpt from Ace of Aces

Chapter 21

A NEW AERIAL TACTICMAJOR BROCARD called a meeting in Dunkirk's best hotel. "Prepare your maps and conserve all your energy," he said, "for there is a big job to be done over there." This region of Flanders, so rich and flat, was a tough assignment for the "Storks" Furthermore, our first reconnaissance flights did not show it to be very gracious. We had before us, at the extreme boundary of the front line, a spongy terrain where the water sneakily infiltrated the slightest holes - a muddy swampland where bogged- down tanks disappeared entirely without leaving a trace. Our infantry comrades were not able to dig trenches.

Mounds of sandbags outlined the plain winding lines, and the overflowing Yser River remained for five years the impenetrable barrier before which the invader was stopped.

Shells penetrate the earth and often do not burst. When an explosion is produced, it projects a veritable outpouring of mud in all directions, and soon, around the newly dug crater, a characteristic bubbling indicates that another pool is in the process of being made. To stay put in these regions, it is necessary to have solid morale and a temperament indisposed to rheumatism. Perpetual fog adds further to the impression of sadness which invincibly comes from this countryside where the eye does not find a landmark worthwhile enough on which to concentrate.

The premature death of Rodenbach undoubtedly deprived us of an admirable poem. The author of Bruges La Morte truly expressed the poignant melancholia of this country. He alone would have known how to write the glorious chronicle of the armies' gathered on the banks of the Yser.

The enemy did not seem to suspect anything. I flew over Ostende without difficulty at first, and even Zeebrugge, where the enemy submarines had their main hiding places. My first patrol missions would have been devoid of interest if I aid not have as a distraction the flights of the Angto-French flotillas which constantly guarded the coast a short distance away. Soon, however, the enemy sent up their best fighter squadrons to meet us. They surprised us with their new combat tactics, and it immediately became a very rough situation for us. We were attacked at all altitudes and at all times.

Fritz was admirably protected by his antiaircraft batteries. Our reconnaissance squadrons were worn out Every day the planes returned riddled with holes, and often the pilots were wounded as well. I knew sunny days when the entire atmosphere vibrated with the sound of propellers. The report room was never empty. Each minute a pilot in flight uniform came to describe the details of his last combat.

The Boches developed a new tactic. They brought out of hiding a new flight pattern. We now had to deal with groups of fighters trained to maneuver together. Each of us successively were at grips with eight, or ten Fokkers at one time. Our great aces, taken unaware, were hit quite seriously, and some never returned. Little by little the survivors felt the superiority of the air slipping out of our hands. Heurtaux, Deullin, Auger, and Matton were wounded or dead. (Captain Matton and Captain Auger were killed in Flanders.) Guynemer, the immortal hero, left one morning never to return, and others less well known also marked this painful calvary with their graves.

We had to concede that our old tactic of the lone, isolated fighter plane would no longer work. Consequently, we too decided to create teams, and that's the way it was. It seems that in France a memorandum suffices to remedy all evils, but once drawn, nobody seems to bother about the means of execution. Regardless of the importance of the measure, nobody worries ordinarily about how to apply it.

I, for my part, had some trouble mastering this new method. With the authorization of Captain D'Harcourt, I bad recruited some young volunteer pilots. We left together in groups of six or seven, and I led my pupils in the attack on the Krauts.

I don't even remember bringing down a single plane, but our attempts provoked the intervention of enemy reinforcements eager to protect their comrades. Soon there was a dogfight, and my buddies were obliged to become familiar with the tactic. I was there more or less to support them, and I successively relieved the clumsy ones, but I could not engage in real combat myself, for I would have risked the slaughter of the most inexperienced of my pilots. I let loose a burst here or there, always remaining on the alert. My group thus acquired, very quickly, a great ability to maneuver. Our sorties henceforth continued in triangular formation in groups of three or four. My pilots protected me from attacks in the rear and, for my part, I had the responsibility for the rest of the sky. In this way, we did a pretty good job, and I can boast about not having suffered even the slightest loss. On the other hand, my squadron was the one which had the greatest number of confirmed victories in Flanders.

Chapter 22

THE FLANDERS OFFENSIVE

(JULY 1917)THE Flanders offensive was in full swing. The merged armies were grouped pell-mell - English, French and Belgians. In the air the fusion was complete, and it was not rare to find a patrol where the three Allied nations were represented.

An August 9, Captain D'Harcourt, at the head of the entire Squadron, was flying protective cover for a bombardment operation. We were flying over Dixmude at an altitude of 3000 meters and were about 10 kilometers inside the German lines, when we ran into two groups of enemy fighter planes, each one consisting of sixteen Fokkers. Never before did I have such a picnic.

Accompanied by a few comrades, Captain D'Harcourt quickly went to the assistance of some of our bombers that were having a rough time. It would be impossible for me to describe all the details of the battle. It was much more than a skirmish at least thirty planes took part in that dogfight.

Two Sopwith two-seater planes (Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter observation planes) not far from me had sustained damage and were in trouble. Their machine guns were disabled. Three German planes realized the situation and were attacking furiously. It was then that I intervened. On my first pass I brought one of them down in flames. The other two were now getting into range, and using a tactical maneuver that was quite familiar to me, I swung over to broadside and again a German plane fell. The third escaped. I now felt that I could join my comrades and set down on our aerodrome.

The month of August was a veritable aerial massacre for the enemy. The region of Nieuport, Ypres, Dixmude and the Forest of Houtulst are now nothing but a vast cemetery where many of their squadrons were engulfed. The number of enemy fighter and reconnaissance planes diminished every day under our blows.

I had become a virtuoso, and having seriously practiced my art, I succeeded in hitting the enemy from every angle, from no matter what position I found myself in contact with him. From that time on, my greatest victories took place.

The "Stork" Group enjoyed considerable prestige. We were the uncontested elite of the Army of the Air, and our reputation had extended even beyond the boundaries of our country.

The Prince of Wales came in person to extend to us his congratulations and to have lunch with us. He was pleased to accept the small silver stork insignia of Spad No. 3 as a souvenir of this occasion. Later the King of Belgium did us the same honor, and by a wonderful gesture which touched us deeply, Queen Elizabeth was gracious enough to accompany him. These sovereigns, whose heroic attitude joined the admiration of the entire world, accepted, as mementos, the stork insignia of the 103rd.

Such visits exalted our courage and inspired even the humblest of us to attempt astonishing feats of daring. The French are built in such a way that the satisfaction of pride moves them more than material reward, and we would have considered ourselves undeserving if some other flying group had succeeded in equaling us.

Persons less distinguished but with whom we felt more at ease were frequently our hosts. We also mingled with our Allied comrades. Thieffry, the great Belgian ace, was often with us; and without his foreign uniform and his accent, the true brotherhood that we showed each other would have resulted in his being taken for one of us.

These receptions were mutual, and I too was often carried off triumphantly to the mess hall on landing at a Belgian or English aerodrome. But these military pleasures also had their drawbacks. Our field at Saint- Pol had been installed in a dry haven which could be easily recognized from the air, thanks to the proximity of the sea. Almost every night, the Boche bombardiers awakened us. The mess hall of Spad No. 3 was hit one day by several bombs, and Guynemer's phonograph, zealously guarded, still shows the trace of it.

Chapter 23

A BLACK DAYSEPTEMBER 11, 1917, must be marked down as a dark day for us. On that day our Air Force lost its most glorious hero. In prose and verse, others have praised his exploits and expressed the grief to the entire country. Parliament voted him the Honors of the Pantheon. But the finest mark of admiration and regret is that which remains forever engraved in the hearts of his comrades- in-arms, each of whom made himself his avenger. Unfortunately, all too many of them fell in this attempt. Guynemer left on patrol at the crack of dawn. It was daybreak, and the first rays of the sun, emerging from the mist, were sparkling on the foliage, prematurely brown because of the coolness of the nights.

While the mechanics were scurrying about to check out his plane, the pilot, a little nervous, as if a secret apprehension was haunting him, was pacing up and down feverishly, like a lion in his cage. "Guynemer is not in a good mood this morning," observed someone, but none of us thought at the time to attach any importance to this reflection. Finally his motor began to turn over, and our companion quickly hopped into the cockpit; the propeller started spinning and, like a great bird, the plane took off. At the same time Lieutenant Bozon-Verduras rose to join him.

What happened after that? Nobody ever learned the exact truth. We only know that they flew together and gave mutual support to each other in several engagements. Lieutenant Bozon, separated from his companion in the midst of combat, lost sight of him and returned alone to our field.

This was not the first time that Guynemer came back late, so nobody thought of worrying, but as the hours passed his absence became more and more the subject of all of our conversations. Major Brocard no longer hid his anxiety. Information was requested by telephone from the front lines, and we soon learned that a French plane had been seen shot down within theBoche lines. The observers said, however, that the plane was not in flames and that the pilot was perhaps only injured.

Two or three days went by and the return of Guynemer became more and more improbable. We hoped nevertheless that he had gotten out of it, and that an escape, or peace, would bring him back to us. But an enemy newspaper deprived us of even this hope. It published, along with the name of the victor. Captain Wissemann, news of the death of our national hero. I was near the hangar when Major Brocard brought us the sad verification. It was a terrific shock and I quickly took my Spad up, determined to seek in the air an escape from my deep sorrow.

Ten minutes after I took off, I spotted a plane in the distance. I recognized it immediately as a two-seater photo-reconnaissance job. Absorbed in their work, its two occupants had not seen my approach. As usual, I climbed very high in order to dive on the enemy. This tactic, instinctive to birds of prey, always seemed to me to be the best strategy. I surprised them in an attitude of complete security, the pilot still at his controls, and the observer in the act of taking photos, bending out over the cockpit waist- high.

I swooped down but waited until I was a few meters away before opening fire. With my eyes fixed on the sight, I quickly saw all the details growing rapidly in size. Aiming directly for the middle of the plane, my bullets raked the area which housed the motor and the aircraft's crew.

It wasn't long before I saw the results. Undoubtedly killed by the first burst, the pilot must have slumped in his seat, jamming the controls in his agony, for the plane immediately began to spin. While rapidly banking to avoid collision, I saw the body of the observer, still alive, falling from the upside-down plane. For a split second he had tried to remain in his seat. He passed only a few meters from my left wing, his arms frantically clutching at the emptiness. I shall never forget that sight.

But the incendiary bullets had done their job, and the plane, like a gigantic torch, went down at full speed, crashing to the earth where the body of the observer had preceded it.

Such was the funeral of Guynemer to me. This my fourteenth confirmed victory.

Chapter 24

GUYNEMER AVENGEDA FEW days later, the Group left Flanders. These misty regions, where rain and fog reign without interruption for months on end, are likely to keep an organization such as the "Storks" grounded for an entire winter. To have kept us tied down any longer would have been a veritable waste of strength. From time to time during the autumn, we were barely able to claim a few victories, and for my latest success I brought down a big reconnaissance two-seater.

I was patrolling on September 30, 1917, at an altitude of 4000 meters with several comrades, when I saw this bold fellow flying below us. He calmly continued his inspection as though his life were somehow magically protected from danger. I immediately opened up the throttle and my Spad leaped forward. That Boche character did not seem concerned :at this, but upon approaching, I saw his machine gun ready for action.

The maneuver required close precision, but I was already an old hand at this game. While still bearing down on him, I caused my plane to make irregular movements similar to those which permit a butterfly to escape its enemies, and my tactics evidently seemed to disconcert him.

I do not subscribe to the historic chivalrous attitude nor the lengths employed by Fontency in his offer to the enemy. This French commander was supposed to have said: "Englishmen, you may fire first." This, to my way of thinking, is a very unpractical method. If the English had then had machine guns at their disposal, probably not a single Frenchman would have returned to report those gallant words. I believe it is necessary to adopt a middle-of-the-road attitude, not to waste bullets but to fire away at the very moment when I have the best chance to score.

Therefore, without answering back, I accepted the fire of the Boche three times, but when my turn came and I fired my machine guns, I immediately had the satisfaction of seeing the enemy plane shudder. I went through some feints, and quickly coming out, I succeeded in placing myself under the rudder of my adversary. Almost simultaneously I caught both the pilot and machine gunner in my fire. From above, I watched their fall. A thousand meters below me, perhaps, one of the plane's wings broke off, and the men were catapulted from their seats. I always felt a little compassion for my victims, despite the slightly animalistic satisfaction of having saved my own skin and. the patriotic joy of victory.

I often preferred to spare their lives, especially when they fought bravely-but, as I believe I once said, in aerial combat there is usually no other alternative than victory or death, and it is rarely possible to give quarter to the enemy without betraying the interests of your country.

Thus, these latest Boches brought down had been admirable. Pilot and machine gunner had not for a moment lost their composure, and seeing me approach, instead of disrupting their reconnaissance mission and turning tail for home at full speed, they had waited for me, courageously accepting combat without batting an eyelash. No sooner did I land than I took a vehicle to go and see my victims and examine on the spot the remains of the plane to learn if the situation called for improvement in my technique. Some officers had preceded me, and the first news that they gave me was that one of the bodies carried papers identifying it as Wissemann, the very same one to whom the German newspapers gave credit as the victor over Guynemer.

A few days later we left for a new sector, and this move had the most fateful consequences for the Group. Our squadron was going to have as its base a little village in the vicinity of Soissons, named Chaudun. All experienced pilots we had sent out despite the storm. A plane is always ready for flight, and I only had to give my faithful mechanic, Grue, two hours' advance notice in order to find my two valises aboard and the plane ready to take off. Grue had been, my orderly for a long time. He had a maternal instinct toward me, and rejoiced at my successes as if he himself was supposed to share in the glory.

Terrible news reached me upon arrival, Tourtel, caught in the fog, was killed in the vicinity of Crepy-en-Valois, and a similar tragedy happened that same day to Captain De la Tour near Amiens. In these unfortunate accidents two heroes who had rendered to the Aviation Service and to their country the most eminent service were lost to France.

They were two faithful friends whose loss I will find it hard to get over.

Chapter 25

VERDUNOUR arrival at Verdun took place on January 19, 1918. We now had as our chief a replacement for Major Brocard, Major Hormant, and if the departure of the former had depressed us, we soon had to recognize that in choosing his successor supreme headquarters had a stroke of genius.

A horse-back riding enthusiast, Maior Hormant had the precise and rapid eye of a rider. He hid beneath his stern exterior a big heart and knew how to formally mitigate a punishment that another might have dealt with more harshly. He was soon adored by all, and this is an essential quality for a group leader.

Superiority in our branch of service is a state of mind. To really surpass the enemy, it is necessary to have almost the equivalent number of planes, and a perfect stability of mind which furnishes the means to dominate him. The pursuer who gives way to preoccupation deprives himself of part of his advantages by this solitary fact. He will lose, in decisive moments, absolute mastery over himself, and that, at the peril of his life and to the detriment of his outfit.

Everywhere we went, the Boches let themselves be outmaneuvered by us. Everywhere we had difficult times at the beginning, but we always came out of it success- fully, to our honor-for nothing was able to distract us from our assignment, and we were certain, whatever the results of our undertakings might be, fortunate or unfortunate, to have the complete confidence of our leaders.

The sectors in which we operated were ordinarily, before our arrival, more or less conceded to the enemy unless the preparation of an offensive seemed to justify a certain activity. First of all, we had to fight against determined adversaries, accustomed to hold their ground as if they were defending their own land; naturally, the first encounters were very fierce. But soon we regained our customary supremacy; and with us to protect them our reconnaissance planes regained their confidence.

To keep us in good shape, our commandant spared nothing. The "Stork" Club had a meeting hall where the most varied entertainment was placed at our disposal. When the weather was bad, we spent endless hours discussing aerial strategy and having a good time like children. If someone suffered from an obvious case ofthe blues. Major Hormant did not take long to realize it, and a leave of absence, offered opportunely, permitted the troubled individual to join us a few days later, with renewed vigor and in possession of all his faculties.

The sacred soil of Verdun, where we were going to operate for some time, literally oozes heroism. It seems that from this very earth, torn by shells, comes a breath of hatred which brings the individual to the most complete spirit of sacrifice. This is without a doubt the reason which influenced the Allied governments to honor this martyred city above all the others. Others have suffered more. I saw Albert, for example. It is nothing but a heap of debris-but Verdun in ruins, a city paved with corpses, must be for the Boches the symbol of our will to win. The leaders of people, whether politicians or officers, who visited it have clearly felt that- and as a reward for this tenacity have lavished on it their choicest distinctions.

The "Stork" Group intended to announce its arrival in its very own special way. At our very first meeting in the mess hall, Captain D'Harcourt suggested a reconnaissance mission, and we enthusiastically endorsed it. I for my part rejoiced, for I heard that the Germans in this region showed plenty of fight, and their bellicose attitudes far from displeased me.

The pattern of our departure resulted in our being grouped purely by chance: Captain D'Harcourt, my good friend Fontaine, two other young pilots, and myself. In starting out we seemed to run into bad luck for our chief almost immediately had motor trouble which prevented him from accompanying us. Ten minutes later, a Boche patrol appeared. From the heights where we were, we immediately dived on them, each one choosing a different target. Fontaine, to my right had two opponents on his hands, and would have really gotten along fine by himself if his motor had not died on him in the middle of a turn. During his diving descent, the two Boches who were now tailing him took the offensive and began to fire their machine guns at him.

It was then that I intervened. I pounced on them like a bird of prey and without giving them the time to break away. With a burst of fire from twenty meters in the rear, I brought down the one who was closer to me. His plane was going to crash into our lines, and his companion, who in the meantime became panic-stricken, took off at full speed. They had nevertheless achieved a certain result: my patrol was dispersed

Fontaine had been forced to land, and my two rookies had gone, I don't know where. I was circling around in the air in order to rally my team when, to my left, a big flame suddenly burst out.

I have not often been present at the explosion of an observation balloon, but it is a moving spectacle that one does not forget when one has witnessed it even once. This fire is the danger that all hydrogen-inflated dirigibles fear. They spoke of a recent development which would permit this gas to be replaced by helium. However, for my part, I never saw our aviation service experiment with it. It would have been desirable however, to have such an improvement in effect, for the observer, who is not able to leave his basket or time, is generally burned alive without being able to protect himself from the flames. I don't like to fight the enemy in this way and I prefer to leave the job of destroying these defenseless fellows to the specialists.

But when the victims are ours, my comrades and I unable to defend them successfully, try at all odds to avenge them. I therefore flew toward the fire and soon spotted four Fokkers who, after the attack, were heading back to their field without too much speed.

More Medals

The poor weather of October, 1917 limited Fonck's flying time, but in just thirteen hours in his logbook, he claimed ten aerial victories (only four were confirmed). He continued to pile up kills and recognition, only going on leave over Christmas to get married. He returned to his escadrille in January, 1918, shooting down an Albatros and a Fokker in one day, his first double kill.

On May 9, 1918, he shot down six German planes. Lingering fog delayed his start that day until four in the afternoon. Escorted by two other Spads, Fonck flew toward the lines, coming upon a Boche camera plane and its two escorts. He promptly dived at and shot down the first, and then the second fighter. As the third German plane tried to escape, Fonck got on its tail and blew it up. Three planes in minutes. He returned to his base and took off again at 5:30. An hour later he emerged from a cloud, below a German two-seater and blasted it. Nine German machines then challenged him. Incredibly he got behind them and picked off the "Tail-End-Hans," for his fifth kill of the day. As the remaining eight tried to maneuver him over their lines, he got one more to make it six in the day. Six in one day!

By August, he had accumulated 55 official kills, and passed Guynemer's score. On the 14th, he shot down three planes in ten seconds; they almost fell on each other. In September, he had another six-victory day. When the Armistice came, he was officially credited with 75 aerial victories, the most of any Allied pilot, a number only exceeded by Germany's Red Baron, von Richthofen. (Fonck himself claimed to have shot down 120, surely an inflated number.)

Postwar

He continued flying after the war. In the mid-Twenties, he sought to fly the Atlantic, the Holy Grail of aviation pioneers, a New York to Paris flight. Teaming with Igor Sikorsky, they prepared a three-engine craft, the S.35. He tested the aircraft for days, but when he first tried the long flight on September 26, 1926, a faulty fuel tank brought him down. A few days later, on a second attempt, the S.35 crashed and burned on take-off, killing two other crew members. Before Fonck and Sikorsky could try again, Lindbergh had made the first flight.

Eventually, his vanity soured his relations with the press, and he lost much of his wartime popularity. In 1939, he retired as France's Inspector of Pursuit Aviation. He died in 1953, at age fifty-nine.

Sources:

- The Aerodrome

- Heroes of the Sunlit Sky, by Arch Whitehouse, Doubleday, 1967

- The Canvas Falcons, by Stephen Longstreet, Barnes & Noble, 1970

- Rand_McNally_Encyclopedia_of_Military_Aircraft:_1914-1980, by Enzio Angelucci, The Military Press, 1983