Scharnhorst

German Battle Cruiser of WW2

By Stephen Sherman, June, 2011. Updated March 21, 2012.

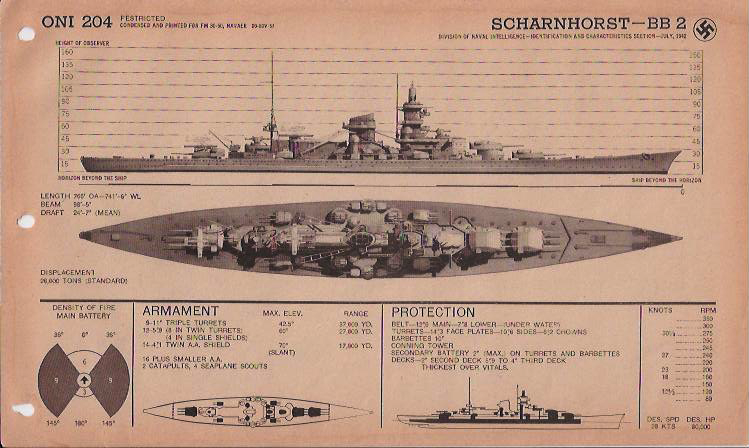

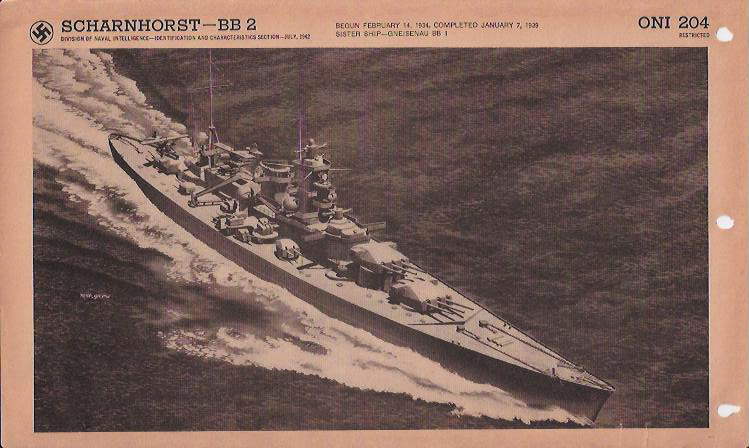

Like the Royal Navy's ill-fated Hood, the Scharnhorst was technically a battle-cruiser, but is generally called a battleship. Scharnhorst presented an imposing silhouette, with three triple turrets, a heavy bridge superstructure, and a single large stack. Her conning tower was set back a little from the two forward turrets, near the funnel. Farther aft were two catapults, the mast, and a single after turret.

She measured 766 feet overall, 741 feet at the waterline. In beam she was 98 feet 5 inches, and drew 24 feet 7 inches of water. Her displacement was 26,000 standard tons.

Armament

Her main battery consisted of nine 11-inch guns in three triple turrets; these had a maximum elevation of 42.5 degrees and an extreme range of 37,000 yards. Her secondary battery was twelve 5.9 inch guns (8 in twin turrets, and 4 in single shields). These could elevate to 60 degrees, and had a maximum range of 27,000 yards. Scharnhorst carried fourteen 4.1 inch anti-aircraft guns, that could fire 17,000 yards, as well as sixteen smaller AA guns. Her two catapults serviced four seaplane scouts.

Protection

A main armor belt of steel from 7.8 to 12.6 inches thick protected Scharnhorst at the waterline. Her turrets were protected by 14.3 inches on the face plates, 10.6 inches on the sides, 6.2 inches on the crowns, and 10 inches on the barbettes. The deck was protected by 4 to 5.9 inches of armor.

Construction and Sea Trials

The contract for Panzerschiff "D" was placed with the Marinewerft, Wilhelmshaven on 25 January 1934. The first keel was laid on 14 February 1934, but in mid 1935 was scrapped due to design changes. A new keel was laid down on 15 June 1935. Construction took 16 months, and Scharnhorst was launched on 3 October 1936. The Scharnhorst was not commissioned until 7 January 1939, more than two years after launching. Her first captain was Kapitän zur See (Captain) Otto Ciliax. Following commissioning she underwent sea trials in the Baltic Sea in early 1939. These trials indicated that modifications were needed to the boilers and overall sea-worthiness. In August 1939 a seaplane hangar was added and the stem was changed. After weeks of training in the Baltic, Scharnhorst returned to her home at Wilhelmshaven in November 1939, now ready to operate at sea.

Sinking of the Rawalpindi

On November 21, 1939 Scharnhorst and her sister ship Gneisenau put out from Wilhelmshaven to patrol the North Atlantic, with the triple intention of diverting British ships from the pocket battleship Graf Spee (operating off South America), possibly aiding the German commerce raider Deutschland, and sinking British merchant ships themselves. The two battle-cruisers headed northwest towards Iceland.

In between the Faroes and Iceland, they encountered HMS Rawalpindi, a British converted merchantman. Armed with eight World War One era 6-inch guns, the old ship (built in 1925) had no chance against the two modern German battle-cruisers, which together carried eighteen modern 11-inch guns. At first, Rawalpindi's Captain Edward Coverley Kennedy thought the Scharnhorst to be the Deutschland, and he radioed that information to Home Fleet at Scapa Flow.

As ordered, he attempted to evade the hostile warship by heading for a fog bank. When the Gneisenau appeared and cut off that escape, Kennedy knew it was all over. "We'll fight them; they'll sink us, and that will be that. Good-bye."

The German battleships signaled Rawalpindi, "Heave to." That was ignored. They closed range and signaled again, "Abandon your ship," as they were about to sink her. With possibly misplaced foolhardy courage, the Rawalpindi actually opened up first, firing six-inch shells at the German ships. They did little damage. The Germans promptly opened up with powerful eleven-inch guns, which began to destroy the Rawalpindi. One of the first shells hit the boat deck and bridge. Others rained into the main gun control station and engine room. Soon, injured were all over, fires raged, and Rawalpindi lost power. The order was given to "Abandon ship." At 16:00, as the crew clambered into life boats, one of the German shells hit the forward magazine. It blew up, broke the Rawalpindi in two, and she went down.

Most of her 237 man crew were lost; only 38 survivors were rescued by German ships.

As the action drew to a close, two Royal Navy cruisers approached, with three RN battleships (HMS Warspite, HMS Hood, and HMS Repulse) on the way. The Scharnhorst drew off to the northeast and Norway. Under cover of a rain storm, she shook off the British pursuers, and she steamed south for Wilhelmshaven. Both ships arrived there safely on November 27, having suffered modest damage from the wind and heavy seas.

Invasion of Denmark and Norway

On April 7, the Germans invaded the two Scandinavian countries, assembling all their available naval forces to participate. Scharnhorst, one of the largest German capital ships in the North Sea at that time, was assigned to cover the invading force of cruisers, destroyers, and transports. She put out on November 7 and headed north, along the Norwegian coast. Bad weather and heavy seas shook the ship, and did a lot of structural damage, even without any injury inflicted on her by the Royal Navy.

On the 9th, near the Lofoton Islands, Scharnhorst encountered the British battle-cruiser HMS Renown. The two ships exchange a few shells, and then Scharnhorst lost her fire control radar; she used her faster speed to escape to the west. A few days later she headed for, having suffered further and considerable damage from the rough seas. Her forward 'A' turret had taken in water, which short-circuited the ammunition hoist motor. She docked in Wilhelmshaven on April 12.

Sinking of Glorious, Acasta, and Ardent

On June 8, off the northern coast of Norway, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau caught HMS Glorious, a RN carrier, and her two escorting destroyers, HMS Acasta and HMS Ardent. In a three-hour running battle that afternoon, they sank all three ships.

This engagement highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of the three ship types involved: aircraft carriers, battleships, and destroyers. While very powerful at long range, aircraft carriers caught by capital ships within artillery range were extremely vulnerable. Battleships, with accurate, radar-controlled, large-caliber guns, were still deadly if they could get within 15 miles of their adversary. Destroyers, if bravely and cleverly handled, could interfere with and damage battleships, using their torpedoes, smokescreens, and maneuverability.

By late May, the British forces in northern Norway were in an untenable situation and had been forced to retreat. The Admiralty assembled a large convoy with covering warships and undertook the evacuation. Included were the aircraft carriers Ark Royal and Glorious. Once they had pulled away from Norway and were well out at sea, Glorious' captain asked to leave the convoy and make directly for Scapa Flow.

It is unclear why he left the safety of the larger force and the Ark Royal. Possibly Glorious' fuel situation called for a more direct route; possibly he was anxious to get on with court-martial that had been called after an earlier action; possibly his complement of 10 Hurricanes, 10 Gladiators, 9 Sea Gladiators, and 5 Swordfish was urgently needed in the Battle of Britain. Whatever the reasons, it was a fateful move for the the three ships and their crew. It IS clear that the British ships were not in a high state of readiness: no aircraft were flying CAP, there were not enough lookouts, and only 12 of Glorious 18 boilers were operating. As the ships were zig-zagging to avoid submarines, that interfered with Glorious' ability to launch aircraft.

First contact was reported on Scharnhorst at 16:46 PM (many hours of daylight left in high latitudes in the month of June), and the ship was identified as a British aircraft carrier. By 17:32, the range had closed to 28,446 yards and the Scharnhorst opened up. Both German ships were building up speed, to 29, 30, 32 knots.

Meanwhile Glorious had picked up the Germans at 17:01, and transmitted this report to HQ: "Two battle-cruisers bearing 308° distance 15 mile on course 030°. My Position [approximately] 69°N 04°E." She was trying to get up speed by firing up her remaining boilers and bringing Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers up on deck. As it happened, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were to windward, which compelled Glorious to steam towards them if she wanted to launch her airplanes. The Acasta and Ardent had been steaming on either side of Glorious and slightly ahead of her. Ardent, being closer to the enemy, valiantly interposed itself between Glorious and the German warships, pouring smoke out of the funnels, thus laying an effective smokescreen. Acasta, while further away, also poured smoke. By 17:34, the first Swordfish were on deck, armed with torpedoes.

But just a few minutes later, at 17:38, the third salvo from Scharnhorst, at a range of 26,450 yards, hit Glorious, one of the longest recorded hits in the history of naval gunfire. It put a hole in Glorious' flight deck, essentially eliminating her combat effectiveness. Nonetheless, Ardent and Acasta gamely stayed in action, firing their 4.7-inch guns, launching repeated torpedo spreads, and laying thick smoke, hampering the big ship German ships. For almost an hour, the unequal duel went on. But eventually, superior firepower prevailed and Ardent was hit repeatedly, listed heavily, and then sank, going under at 18:22. With one less destroyer in the way, the German ships poured more heavy shells into Glorious, which burned furiously until she , sinking her by 19:08.

Acasta stayed in action, repeatedly firing torpedoes at the German ships. Finally, at 18:39 one hit Scharnhorst, ripping a great hole in her hull, and putting 'C' turret out of action. But it did little to stave off the battle-cruiser's massive firepower, and by 19:20, Acasta had been hit too many time and sank beneath the waves.

There were few survivors. Together the three ships carried over 1500 men; only 46 were saved. All the others perished in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. The German ships, threatened by other Royal Navy action, did not stop to rescue survivors. The British Navy, apparently unaware of the catastrophe, made no effort at rescue.

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau returned to their base at Trondheim on June 10.

Operation "Berlin"

From January through March, 1941, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau broke out into the Atlantic and attacked Allied sinking. It was a highly successful cruise, as the two ships sunk or captured 22 Allied ships, with minimal loss of life on both sides.

The Scharnhorst at Brest

From March, 1941 through February, 1942, Scharnhorst sat in port at Brest, a target for British bombers. The Germans worked ceaselessly to protect and camouflage her, even building a miniature replica of the port to decoy the RAF. In late July, it was decided to move Scharnhorst to La Pallice, which had few anti-aircraft defenses. Within a few days, the RAF had located her and bombed her on July 24, with great effect. Five bombs penetrated her decks and inflicted damage that took four months to repair.

Operation "Cerberus" - The Channel Dash

In February, 1942, Hitler had one of his hunches, this being that the British were about to invade Norway. Thus, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were needed in the North Sea, rather than in the dubious safety of Brest. In a daring 24-hour run, the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen slipped by the British on February 12, 1942. Admiral Otto Ciliax was in command of Operation Cerberus.

Theoretically, the advantages seemed to be all with the British. Brest was under continuous observation by British aircraft: xx during daylight and Hudson bombers equipped with Air to Surface Vessel (ASV) radar at night. The western end of the Channel was also patrolled by the RAF Fighter Command. As it happened the Germans got lucky. Not only had their assembly of capital ships, destroyers, and schnellboot (comparable to American PT boats) gone unnoticed, but as the convoy got underway at 23:xx on the night of February 11, the RAF's radar-equipped planes encountered one problem after another. None of them were operating over Brest and the western Channel on the night of February 11-12; the Germans put out just after midnight, and already had a leg up, and were off Le Havre by 10:00 AM.

RAF fighters also regularly patrolled the English Channel, frequently mixing it up with Adolf Galland's fighter force. At 10:42, two RAF pilots, Group Captain Victor Beamish and Wing Commander Finlay Boyd, spotted the large German warships steaming east through the Channel. Observing strict radio silence, the pilots headed back to base at Kenley, and informed fighter command. Vice Admiral Ramsay was not informed until 11:30.

By now, the Scharnhorst and the rest were off Boulogne. On this day, the Brits were confounded by communication delays, and precious minutes ticked away. It wasn't until 12:25 that Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde's six Fairey Swordfish biplanes also joined in the attack, but this was no Taranto. With Fw190 and Bf109 fighters swirling overhead and antiaircraft fire filling the skies, the antiquated little wooden-framed biplanes had no chance to torpedo the swift-moving German warships.

Bomber Command seemed to have been the last to know. Not until 14:20 did the first bombers take off. Others soon followed, but of the 242 aircraft in the bombing missions, none hit the ships.

The Royal Navy's surface forces also reacted, but on such short notice, only Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) and some destroyers were able to approach the Germans. These ships tried to attack the capital ships, but were also beaten off by the German air cover and schnellboot.

By 14:00 the Germans had cleared the Straits of Dover; they were by no means out of danger, but they were definitely on the downhill part of their dash. But they didn't escape unscathed. At 14:31, the Scharnhorst hit a mine and slowed to a halt. Admiral Ciliax was forced to switch to destroyer Z29, a hazardous move in the North Sea under the threat of imminent attack. Scharnhorst's chief engineer, Walther Kretzschmar, undertook emergency repairs, and within half an hour, she was under way.

By 17:30, the German fleet was off Rotterdam, and heading for safety. The Gneisenau's turn was next, and she struck a mine at 19:55; she also lay dead in the water for half an hour until she got moving again. Soon the German fleet was more-or-less reassembled off Holland. It seemed like they were home free, but at 21:35 once again Scharnhorst struck a mine.

Scharnhorst finally steamed into Wilhelmshaven on February 13; it was an apparent triumph, but useless, as it was in support of Hitler's defense of Norway against an illusory British attack.

Operation "Ostfront"

By December, 1943, the German situation in Russia had deteriorated badly, and disruption of Allied convoys supplying the Soviet Union was critical. The Luftwaffe didn't have the capability, and other capital ships were committed (or had been sunk). Thus it fell to Scharnhorst to attack any convoys that it might reach. Under the command of Konteradmiral Erich Bey, she set out early on December 26, 1943 to go after Convoy JW 55B off northern Norway. Unfortunately for Scharnhorst, the British had broken the German radio code and found out her location. Admiral Burnett, commanding the three cruisers Norfolk, Belfast, and Sheffield escorting the convoy, placed his ships between the convoy and Scharnhorst's expected direction of attack. Fraser in the powerful Duke of York (a King George V class battleship), along with a cruiser and four destroyers, moved to a position southwest of Scharnhorst to block a possible escape attempt.

It was an uneven battle from the start. First, Burnett's cruisers struck first, knowing Scharnhorst would be coming from. She was hit twice by 8-inch shells; the first failed to explode and caused negligible damage, but the second struck the forward range-finders and destroyed the radar antenna. The aft radar, which possessed only a limited forward arc, was the ship's only remaining radar capability. For the rest of the day, Scharnhorst would be fighting "half blind."

Scharnhorst and the three cruisers maneuvered and exchanged gunfire for three hours, the Norfolk sustaining some damage and the German ship too. But by 13:15, Bey had had enough; he ordered his destroyers home and made for port himself.

With their superior radar, the Royal Navy ships were able to read her moves, and the Duke of York came within range, and opened up at 16:50. The two ships exchanged salvos for two hours, the Scharnhorst getting the worst of it, as Duke of York's 14-inch guns out-ranged her 11-inchers. After her secondary armament (twelve 5.9 inch guns) were put out of action, the British destroyers were able to close within torpedo range and add to the destruction. By 18:42, Scharnhorst had had enough and began to withdraw. With her superior speed of 30 knots, the British commander at first thought that she would escape. But a shell from Duke of York had damaged a critical line to one of her boilers and Scharnhorst began to falter. The British noticed this, promptly re-engaged, and finished her off with gunfire and torpedoes.

Re-discovery

In September 2000, an expedition to find Scharnhorst undertaken by the BBC and the Norwegian Navy. The dive ship Sverdrup II surveyed the ocean floor. Once it located a possible object, the Norwegian Navy's underwater recovery vessel Tyr examined it more closely. The wreck was positively identified on September 10. Scharnhorst went down almost one thousand feet of water. The hull rests upside down on the ocean floor, with masts, range-finders, and other debris spread around the area. Severe destruction from gunfire and torpedoes is apparent. The bow lies in a twisted heap away from the ship, presumably blown off by explosion in a forward turret.