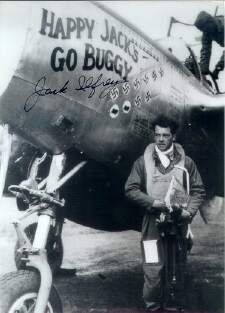

Jack Ilfrey

P-38 Ace

By Stephen Sherman, Dec. 2007. Updated July 21, 2011.

Jack M. Ilfrey was born in Houston on . (The AFAA says 1918; other internet sources say 1920.) While attending Texas A&M College, he enrolled in the Civilian Pilot Training program and then entered the U.S. Army Air Corps in April, 1941. He graduated from flight training on 12 December 1941 at Luke Field, Arizona, and was assigned to the 94th "Hat-in-the-Ring" Squadron of the 1st Fighter Group.

1st Fighter Group

His first assignment was to patrol the California coast in P-38's.

Ilfrey prepared to go to England with the group in the spring of 1942. The jump-off point for "Operation Bolero," a mass flight of fighters and bombers to England, was Dow Field, in Presque Isle, Maine. On July 4th, the P-38's and B-17's took off from the United States, en route for Goose Bay, Labrador; from there they headed for Reykjavik, Iceland. It was on this second leg, that some planes were forced down in Greenland. One of these P-38's, dubbed "Glacier Girl," was dug out of the ice (270 feet deep!) in 1992 and restored to flying condition in 2002.

By late July, most of the 94th Squadron had arrived at Kirton, in Lindsey, Lincolnshire, England, which they shared with the Polish 303rd Kosciusko Squadron. On September 1, the 1st Fighter Group made its combat debut in a fighter sweep over France.

Wild "Portu-Goose" Chase

In early November, the 1st Fighter Group learned of the invasion of North Africa. On the 8th, Colonel John Stone, 1FG CO, briefed them on their next mission: a non-stop 1500 mile flight to Oran, Algeria, noting that Gibraltar would be the only possible emergency stop. Gibraltar was "only" 1200 miles away. Their planned route took them across the Bay of Biscay, near the northwest corner of Spain, down the Portuguese coast, through the Straits of Gibraltar, and then to Oran. As the airfield at Gibraltar was always over-crowded, Col. Stone emphasized that they should only stop there for critical emergencies. On November 15 at 0630, in a fully-fueled Lightning, feeling like a guinea pig, Ilfrey took off from Chivenor Airdrome in Land's End. After a half hour of low-level flight, he felt a slight jolt - one of his 150-gallon belly tanks had fallen off. Under strict radio silence, Lt. Tony Syroi edged close to Ilfrey and displayed a hand-lettered sign "ONE BELLY TANK." Ilfrey signalled his understanding and re-calculated his options. After looking at his maps, he estimated that he could reach Gibraltar. The flight of planes, led by a B-26, headed west to avoid some thunderheads. Shortly, Ilfrey realized that he had to cut loose from the flight and head toward land; he was just too low on fuel. As he turned back east, he further realized that he wasn't going to make Gibraltar. He would have to choose between ditching at sea or landing in Portugal or Spain. Recalling that the Portuguese were not quite as Axis-oriented as the Spaniards (whose leader, Franco, owed his victory in the recent civil war to German and Italian aid), Ilfrey was relieved to spot an airfield near Lisbon.

As he touched down, six horsemen with plumed hats, sabers, and pistols rode out to greet him, and gestured him toward the administration building. He did so and a crowd quickly assembled. An English-speaking official greeted him and led him into the building. The nineteenth-century style cavalrymen were ordered to watch his P-38. Inside, Ilfrey noticed a number of German airline pilots. When a big car screeched up and disgorged more officials, a real interrogation began. After an hour or so, he was informed that Portugal, as a neutral country, interned all combatant airplanes and pilots. This prospect did not appeal to Jack Ilfrey at all.

A Portuguese Air Force pilot expressed interest in the P-38; he had never seen any American fighter plan, let alone the large, unique P-38. They planned to fly the P-38 to a military airbase and refueled it. The pilot asked Ilfrey to explain the controls to him. Feeling somewhat guilty, he did so. As the Portuguese aviator sat on the wing and hundreds of people milled around, another Lightning came over to land. The cavalry galloped off to receive it and the crowd headed toward the new arrival.

Suddenly Ilfrey saw his moment and threw the throttles full forward. The Portuguese aviator tried to reach in to stop him, but the Lightning picked up speed and the propwash blew him off the plane. The bystanders' hats blew all over the place; Ilfrey slammed shut the canopy and headed back down the runway. As taxied and took off, he recognized the incoming Lightning as that of Capt. Jack Harman.

Airborne again, he was relieved, but still shaken; he had no parachute, no Mae West, and no maps. In the bright sunlight, he headed for Gibraltar, ignorant of the diplomatic firestorm he had just touched off. He spotted "The Rock" without any difficulty and touched down at Gibraltar's airfield, squeezed up against a border fence where German lookouts monitored all the air traffic. He told his story, to amazed squadron mates and then to an infuriated Colonel Willis, CO of American operations at Gibraltar. Col. Willis chewed him out for not destroying the plane, for not thinking, for creating an international incident, etc. etc.

Ifrey suspected that the authorities wouldn't throw him back to rot in a Lisbon detention center, although that possibility was greater than the optimistic, exuberant young pilot imagined. When Col. Willis informed him that indeed was Washington's directive, Ilfrey was incredulous. But Col. Willis took care of him, cabling Washington that the pilot in question had already left for North Africa. That day, Ilfrey did so. As for Jack Harman, as soon as he landed the Portuguese grabbed him by the neck and threw him in jail, with no opportunity for him to "demonstrate" his aircraft.

This anecdote is recounted in greater detail in Aces in Combat: The American Aces Speak, Vol 5, by Eric Hammel.

Ilfrey redeemed himself for all the trouble he had by shooting down several German airplanes. Flying a P-38 Lightning nicknamed "Happy Jack's Go Buggy," he shared credit for an Me-110 shot down returning from a strike on Gabes Airdrome on 29 November 1942. Just three days later he destroyed two Bf-109s over Gabes Airdrome, Tunisia, and on the 26th, while leading a flight over Bizerte and Tunis, he downed two FW-190s. On 3 March 1943, he achieved ace status, when he shot down a Bf-109 in the Tunis area.

Returning to the U.S. in April 1943, Ilfrey reported to the replacement training unit at Santa Ana, California where he trained pilots in the P-38 and P-47.

20th Fighter Group

Promoted to Captain, in March 1944 he went back to combat in England as commander of the 79th Fighter Squadron, 20th Fighter Group, based at Kingscliffe. There he scored two more victories, a pair of Me-109s downed over Elberswalde on 24 May 1944. Shot down by flak while train-strafing on 12 June, he evaded the Germans by hiding in the hedgerows that dotted the French countryside. Hidden by a French family, he eventually made his way back to the Allied lines, riding a bicycle and taking the identity of "Jacques Robert", a deaf-mute Frenchman.In two combat tours, he flew 142 missions.

Ilfrey left the service following World War II and returned to his native Texas, where pursued a career in banking. Jack Ilfrey passed away .

Aerial Victories: 7.5 confirmed and 2 damaged.

Medals: Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross with 5 OLC's and the Air Medal with 13 OLC's.

Source: American Fighter Aces Album, copyright 1996 by the American Fighter Aces Association, Mesa, Arizona